The Life and Times of Hesyre, the First Recorded Physician and Dental Surgeon in History

Dr Roger Forshaw

January 2025

Dr. Backhouse began by explaining that she was going to be looking at what we actually know about Nefertari and Ramesside Queenship. A very interesting topic, given that we feel we know a great deal about 18th Dynasty queens, but it is not in fact until the 19th Dynasty that we have queens being buried in the Valley of the Queens, which makes them so much more visible.

We know that Ramesses II’s most notable wife, his Great Royal Wife, was Nefertari and that together with Isetnofret they are the mothers of his favourite children. Images of the children of both are depicted concurrently, though we never see both Nefertari and Isetnofret in the same scene.

It is likely that Ramesses II married Nefertari whilst he was still the Crown Prince, but we know nothing of her life beforehand other than that she came from a family which moved in the elite circles at court. We see her from year 1 of her husband’s reign taking part in cultic activity and from the start of his kingship she is involved in both political and religious roles, being his constant companion. She accompanies him on many of his statues, although as many of these are usurped, and often from Amenhotep III’s reign, the lady depicted originally was Tiye.

Her titles give clues to her diverse roles – political, religious and personal. As the political Nefertari she is Mistress of the Two Lands, wife of the Strong Bull, Lady of Upper and Lowe Egypt, whereas God’s Wife is descriptive of her religious obligations. In personal terms she is described as hereditary noblewoman, sweet of love, great of praises, lady of charm and great royal wife his beloved.

There are many carved examples in temples of Nefertari carrying out cult activities, but she is the only Ramesside queen who is shown at a Window of Appearance taking part in the ceremonies with the king. She is also recognised on the international stage, with letters found showing exchanges with the Hittite queen.

One of the greatest dedications to Nefertari is of course at Abu Simbel. On his own temple there Ramesses II has various female members of his family represented by his ankles, but the prominent position is reserved for Nefertari. But the smaller temple is actually dedicated for her and two of the statues fronting the temple are of Nefertari. It is extremely unusual to see a queen on the front of a temple, however Ramesses II also include four statues of himself! There are more highly unusual scenes inside the Abu Simbel temples with Nefertari attending at a smiting scene, although she does not take part herself (as Nefertiti did). In the inner sanctum of the smaller temple there is a unique and remarkable scene which appears to show Nefertari being crowned by Isis and Nephthys, which parallels a similar scene in the larger temple with the same act taking place for Ramesses II between Seth and the local form of Horus. Another scene shows the king and queen worshipping one of the gods together; an ultimately powerful image. On the Stela of Heqanakht there the lower register shown a seated Nefertari receiving devotions, whilst Rameses II, offering to the gods on the upper register, is followed by one of his daughters. Could this be an indication of some frailty on Nefertari’s part? She disappears from the record between regnal years 24 and 30.

Nefertari has an exquisite tomb in the Valley of the Queens, the Place of Beauty, which had previously been used for burials, but not for that of queens. It was rediscovered in 1904 by Schiaparelli but had been disturbed long before this. Prior to the 19th Dynasty New Kingdom queens had been buried either in an undecorated chamber in the king’s tomb or in an undecorated tomb of their own in the Valley of the Kings. Nefertari’s is the largest and most sumptuously decorated of the tombs in the valley, with a complex architectural design, and the extensive and beautiful decoration tells the story of her transformation as well as ensuring that she has a successful afterlife. Images of Nefertari show her with darker skin tones than usually used for females, which may refer to her need to become an Osiris – the road to rebirth for all at this time period. Her skin is also shown shaded, rather than straight block colour, which was the norm, again perhaps relating to rebirth. At one point Thoth is depicted conferring scribal proficiency on Nefertari, who will need this skill to read and recite the names of the Announcer, Guardian and Gatekeeper as she passes through the series of gates leading to the Duat.

Dr Backhouse concluded the lecture underlining that this was a fascinating period for Queenship in Ancient Egypt’s history with very visible markers on the landscape and a significant shift in the archaeology with the new treatment of tombs for the queens.

Febuary 2025

In her recent research Dr. Finch has been looking at Ancient Egyptian medical remains alongside other pathologists and dentists also looking at similar matters. She found that examining Ancient Egyptian medical papyri and other sources generated tremendous insight into how the Ancient Egyptians treated illnesses.

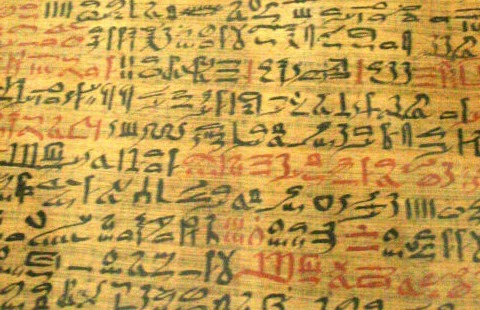

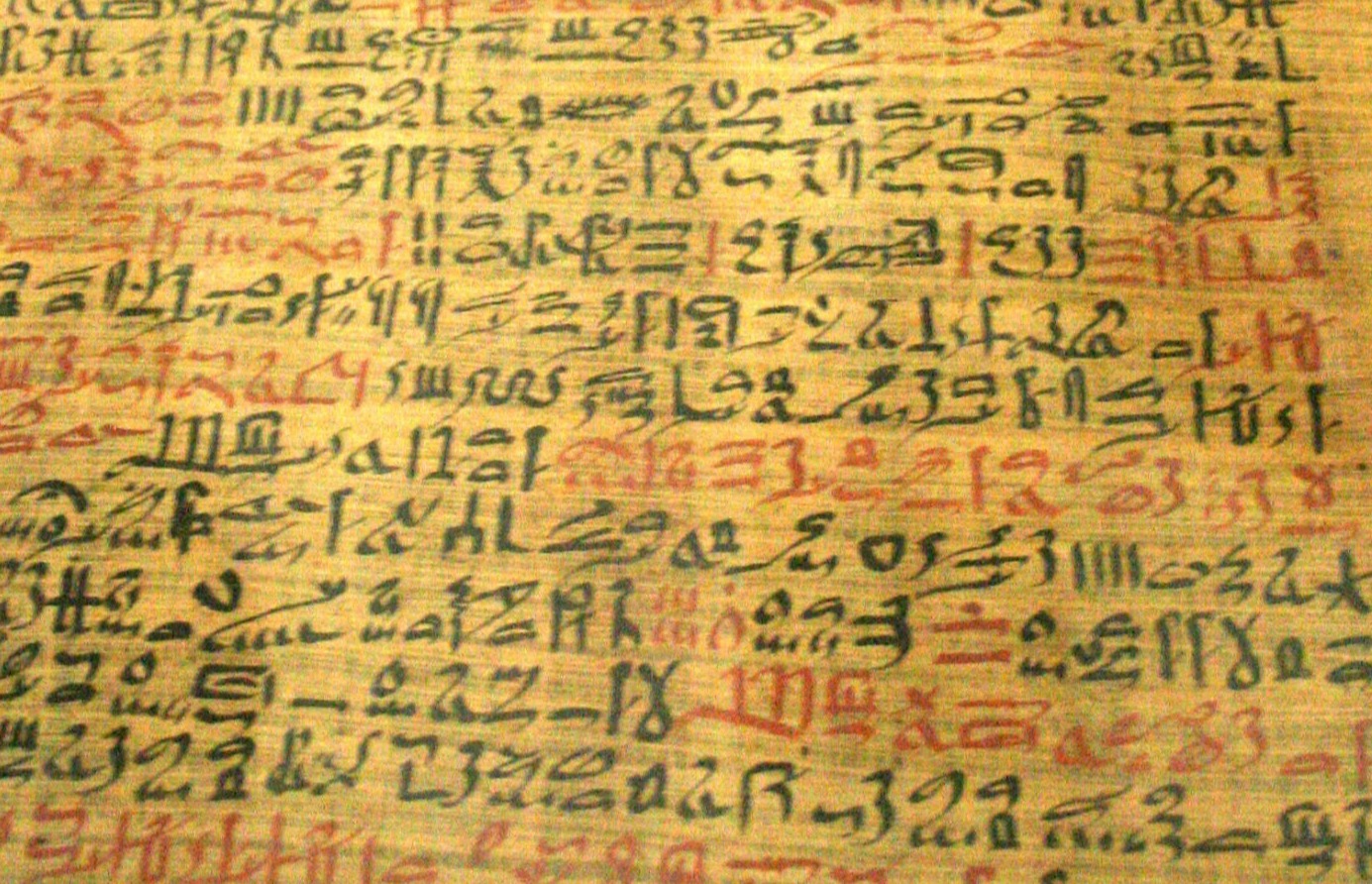

Clement of Alexandria (2nd Century AD) wrote six books of medical interest mainly on the diseases of women. At Kom Ombo reliefs on the walls show medical instruments. Many medical papyri give glimpses of medical procedures and practices alongside details of anatomy, diseases, diagnosis and remedies including herbal ones, surgery and magical incantations.

The Edwin Smith papyrus, produced around 1500BC, is of great importance in this regard and can now be found in the New York Academy of Medicine. It was found near Thebes and sold in 1862 to Smith. It has 17 pages but is not complete. It lists a variety of ailments and treatments, but also includes ailments not to treated. 48 conditions are looked at starting from the head and stopping at the waist, so it is clear from this that it is incomplete. Number 4 says not to bind the head, number 6 says just use ointment without binding and no use of plaster, number 7 (relating to a fracture) says bind on fresh meat, apply a honey ointment and stay sitting. Number 33 describes how to treat a crushed vertebra in the neck and asks is the patient unconscious or speechless(?), can he move his arms or legs? - then decides no treatment should be applied as he will not recover.

The Ebers Papyrus, also found in Thebes and in 1872 sold to Georg Ebers, is made up of 110 pages. Written in about 1534BC in the 9th year of the reign of Amenhotep I it looks at gynaecology, obstetrics, purging and worms. Similar are the Hearst Papyrus and the Kahun Medical Papyrus, which covers gynaecology, pregnancy and paediatrics. One recommends using suppositories or pessaries made of honey and crocodile dung as a contraceptive. The Ramesseum Papyrus looks at diseases of children and women and at conduits moving fluid round the body. The London Papyrus, found in 1860, contains 25 paragraphs of medical information and the Berlin/Brugsch Papyrus has 24 pages on breast disorders, pregnancy, children’s illnesses and birth control. Similarly the Carlsberg VIII Papyrus considers diagnosing pregnancy and ensuring a child’s gender.

More practical medicine is found in the Brooklyn Papyrus which looks at snake, spider and scorpion bites and stings and is believed to be a 30th dynasty copy of a Middle Kingdom 13th Dynasty medical treatise. The Papyrus Oxyrhynchus contains parts of the Hippocratic Oath.

The Chester Beatty VI is described as a ’rather special’ papyrus. It is from the 19th Dynasty and was purchased by Alfred Chester Beatty, a prospector, mining magnate and philanthropist, who gifted it to the British Museum. It looks at diseases of the anus and their treatment. There are 41 prescriptions, many similar to those in the Ebers Papyrus. Conditions considered are prolapse of the anus, expelling worms, reducing swelling, pain, bruising, flatulence and blood loss. Suggested treatments are using honey, juniper and wormwood as an ointment, using flour, bryony root, senna and dates as a laxative, antimony for bleeding and many others. Sometimes instructions are given to pound these together to make suppositories, pessaries or pills to swallow. The fluid in the conduits can carry these medicines, or the illnesses, around the body. A cure for round worms or tape worms was to mix pomegranate juice with other laxatives, leave it to stand overnight then drink.

So, what do we learn from these early studies? It is evident that early Egyptian practitioners had knowledge of anatomy, observation and diagnostics, physiology, treatment and prognosis, prescriptions and the use of magic. In a tomb at Deir-el Medina inscriptions show incidents of the treatment of trauma; for instance using splints on a broken leg. Dr. Finch showed diagrams from an Australian PhD study showing an examination of which parts of the body were recognised by Ancient Egyptians. She then looked at the idea of conduits connecting all parts of the body, as seen in the Ebers Papyrus, which describes them as six leading to arms, two each to the testicles, nose, ears, buttocks, lungs, forehead and eyes, plus four each to the liver and rectum. All of these ancient doctors described the connections as going via the heart, anus or rectum. When it came to measuring medicines they used volume based on the eye of Horus, representing unity, with cups showing measures on the side. It is clear that there were different doctors who specialised in different parts of the body.

Herodotus describes there being a Shepherd of the Anus as an example. And it is interesting to note that many of the herbal remedies are still being used today such as senna pods as a laxative, and then, as now, gut health was taken very seriously.

March 2025

Dr. Slinger shared with the Society details of her interesting and extensive PhD research into the placement and distribution of New Kingdom tombs in the necropoli in Thebes.

She looked at the sacred landscapes along the processional routes, especially that of the Beautiful Festival of the Valley, which followed a route from Karnak across the Nile to the West Bank. During the festival people would go to their family tombs and enjoy banquets with both the living and the dead. The tombs of nobles surrounded and lined the route and were placed as close as possible to the royal tombs between the disembarkation point from Karnak and Deir el-Bahri. Over time these tombs spread into the surrounding areas; Dra Abu el-Naga, Qurnet Murai, Shiekh Qurna, el Asasif and el Khokha.

Dr. Slinger’s research covered 5 main areas :

1. How did the Theban necropolis evolve over time?

2. Were there individual family tombs?

3. Is there evidence of occupational clusters of tombs, for example priests or scribes?

4. Were individuals buried around supervisors; officials around their Viziers?

5. Did being in sight of mortuary temples or the route of the festivals influence where tombs were built?

She firstly created a data base of burials and their placings using GPS to pinpoint their exact locations. This helped in linking the titles of tomb holders together to check for evidence of associations. Prior to Hatshepsut only a few 18th Dynasty tombs were found near the tomb of Montuhotep so evidence is scarce, whereas by the end of the reign of Thutmosis III more information is available due to the proximity of the mortuary temples found there, with some tombs showing evidence of being reused. A cluster of tombs from the end of the 18th Dynasty have been found in the central area, which became popular along the route of the processional way.

During the reign of Ramesses II there was a resurgence of burials here even though many chose to be buried at Saqqara. However none were buried near Hatshepsut’s temple or near the Ramesseum.

She also looked at tomb reuse, finding that many Middle Kingdom and Ramesside tombs were reused, some by family members but also some by unconnected strangers, probably due to a lack of resources.

Many occupational groups were buried in clusters: priests, temple administrators, royal administrators, general and state administrators, local administrators and those with a military title. Dr. Slinger was able to research this, using GPS, to establish that there was a hierarchy to these tombs based on status, with the most important persons having their tombs in the highest spot with the best view of the processional route, especially in Qurna. This might suggest royal or priestly input into who was buried where.

She looked at a series of case studies, the first being the tombs of Viziers, suggesting that the site of their tombs was given to them as a result of their importance; for example tombs TT83 (Amethu called Ahmose) and TT61 (Useramen). Both have a commanding view and suggested that like was buried near like. Another tomb belonged to a Vizier who inherited his position from his father and was entombed near to him. This suggests that tomb sites were chosen by/ granted to a family or workgroup - for example tomb TT100 (Rekhmire). If the Vizier fell from grace, his replacement and his family might take over his original tomb site.

The area known as the Amenhotep II Quarter was linked to him as the burial site of his childhood friend Pairy; another family group buried near to each other with a clear line of sight to his mortuary temple and the processional route. 18th Dynasty Viziers would seem to have had considerable power over who was allocated which tomb site.

When the High Priests of Amun became more powerful tomb scenes became more religious in content and fewer scenes of daily life were shown. Additionally they began to build the tombs closer to Dier el-Bahri, opposite Karnak, as the Pharaoh’s power was decreasing and theirs was growing. Significantly two High Priests converted older structures into mortuary (cult) chapels, demonstrating further how their power had increased.

At Dra Abu el-Naga a separate cluster from the Ramesside period was created with a good view of the processional way from Karnak. There are 17 tombs, 3 of which belonged to High Priests, together with a family group, which shows that the High Priests of Amun could also control who was given burial sites and where. Karnak was visible from Deir el-Bahri and from Dra Abu el-Naga, so these were sought after sites.

So how did these sites evolve? It seems to have been a gradual process where some were used extensively over a long period and some for only a short time. They were influenced by status, desirability of location, spatial connections, resources and available space. During the 18th Dynasty and the Ramesside period links amongst families were important as many positions (Viziers, High Priests, officials) were inherited and so the generations were entombed near each other. Viziers’ tombs acted as focal points, as others wanted to be entombed near illustrious predecessors. That and a view of and orientation towards a mortuary temple or the processional route was an important reason for selecting the site where you would rest for eternity.

June 2025

Colin began his lecture by reassuring us that, despite the title of his lecture, aliens would not be featuring! The extraterrestrial aspect is, in fact, connected to the large yellowy green coloured scarab at the centre of one of the pectorals found in Tutankhamun’s tomb.

Until fairly recently it was thought that the stone was chalcedony, which is not particularly special, begging the question of why it was used for the centre piece. However, analysis by Vincenzo de Michelle has revealed that it is actually silica glass and a very specific type of silica glass; Libyan Desert Glass, which is highly unusual and scarce. Did the court of Tutankhamun use this particular stone because they knew just how rare it was? The only source of this is a very localised area way out in the Western Desert – north of the Gilf Kebir and south of the Great Sand Sea – about as far from Thebes as possible and away across extremely forbidding terrain. It was rediscovered in 1931 by Pat Clayton during his exploration of the desert.

The pale yellow/green substance is translucent and entirely natural. It was thought to have been created by the huge energy resulting from the impact of a meteorite (the extraterrestrial connection). There are numerous examples of such impacts around the globe and indeed close to this area, in Libya and Sudan, including one which produced Dakhla Glass, which is somewhat darker than Libyan Desert Glass. The resultant craters are usually very large and the rock and soil typically melt at 1000C. As the molten material is thrown out of the crater and cools down, glass is created.

But one of the mysterious features of the Libyan Desert Glass site is that there is no crater. The chemical composition of the glass is also highly unusual with more than 95% silica. It might be thought that, as the area is composed of Nubian Sandstone, a high silica content would be expected. But this is, of course, today’s geology. The glass is thought to have been made about 26 million years ago when the geology was considerably different; at that time the terrain was lush green forest covering limestone. Another site across the world provides some clues. In 1908 there was a massive explosion in Siberia at Tunguska – fortunately this happened in an extremely remote location, so there were minimal casualties. For more than a thousand square miles the trees had been laid flat, in a circular pattern. Initially a meteorite strike was assumed to be the cause, but again there was no crater. The alternative explanation given was of a comet entering through the atmosphere and exploding just above the surface. In the Western Desert not far from the Libyan Desert Glass site another extraterrestrial material, hypatia, has also been found. This stone is not part of the composition of meteorites, but is typical of comet material. An exploding comet seems to fit the lack of crater and strange composition of the glass. When the glass finally made its way to Tutankhamun’s artisans they knew it was highly unusual, but can have had no idea of its extraterrestrial origins.

Although it was a huge distance from the glass site to Thebes, the Ancient Egyptians were well aware of the rich mineral resources in the deserts and, from very early on, mounted expeditions to explore and exploit the minerals. In the Western Desert the oases were stopping off points between the Gilf Kebir area and Thebes and Desert Road Archaeology, a relativity recent field of study, has revealed a comprehensive network of ancient caravan routes criss-crossing the desert between the Nile Valley and the oases, then westward to Gilf Kebir and Uweinat and yet further west and south towards Sudan, Chad and Kufra. The Libyan Desert Glass site lies within these caravan routes and this trading network may have allowed the glass to travel to Thebes. Evidence of 18th Dynasty travel across the desert can be found in deposited water jars at way points such as Abu Ballas and Djedefre’s Water Mountain (though the majority of the artefacts at the latter deposit date to the Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period).

Major Ralph Bagnold, in the 1930s, undertook many exploratory trips far out into the Western Desert, testing how well the early motor cars could cope with the terrain compared to camels and published his results, together with highly accurate maps of the area. With each expedition the amount of detail on the maps increased to finally include springs, temporary pools, previous expeditions, ground conditions, topography and sites of rock art. The ‘cave of the swimmers’ at Wadi Sura on the west side of the Gif Kebir came to light again with its intriguing images and, more recently, the Mestakawi cave with its huge numbers of paintings of animals, people and hand prints. It is clear that there are layers with newer painting overlaying older images and the people depicted are various shapes, sizes and colours, which makes us wonder if this area was a trading location even back then with different people and cultures meeting up. What do we know of these ancient people? The climate has changed considerably over the ages varying from very wet to much more arid. There is evidence in the form of hand axes and other tools of people up to 300,000 years ago. Some are of extinct species predating homo sapiens and a recent Oxford expedition even found a hand axe made of Libyan Desert Glass. By 7000 BC the vegetation in the area had shrunk back so that there was very little greenery other than in the oases, the Gilf Kebir, Uweinat and the Nile Valley. Scholars have divided the rock art into six age groups from A-F, although it is very difficult to pinpoint specific dates. The Wadi Sura rock art is thought to belong to group E from around 5500 to 4500 BC. About 4500 BC the climate changed to seasonal monsoons and cattle pastoralists made their living in the desert. The arid state that we know today began at around 3500 BC.

Understanding the imagery in the rock art panels is problematic. There are some large enigmatic headless beasts, upside down people and some completely unidentifiable creatures. Scholars studying this material have wondered if they can see parallels with later religious imagery and have questioned if we are seeing the start of theological ideas. Not everyone agrees and the debate continues.

In 2022 Colin’s book ‘A Gift of Geology’ was published by AUC Press. He is now working on a second book with the working title ‘The Great Sphinx: re-writing the history of the world’s most iconic monument’, which he is hoping to have published in the near future.

August 2025

Judith gave us a fascinating talk last October on Coffins, Masks and Mummy Cases of Greco-Roman Egypt and, at the time, said this would be the last in her series of lectures over the last few years relating to different aspects of funerary art, decoration and practices in the Greco-Roman period, which had been the subject of her MPhil at the University of Liverpool. So we were delighted when she changed her mind and agreed to return again this year to talk to us about the final aspect of her research – cremation and the use of cinerary urns.

For almost everyone in the audience this was an unknown aspect of practices at the last stages of the Ancient Egyptian civilisation, so was highly informative and interesting. As always, Judith’s lecture was richly illustrated and she treated us to many images of objects mostly drawn from finds in the various necropoli in ancient Alexandria.

More information on all of the topics she has covered in her lectures is available in Judith’s book published by Shire.

Judith declared that this really was her final lecture for the Society. Will it be? Only time will tell!

September 2025

Dr Lacovara began by setting the scene in the Second Intermediate Period where control by the Hyksos, during the 15th and 16th Dynasties, covered the delta and stretched down into Middle Egypt. The Theban rulers had been pushed back into a small area stretching from a little to the north of Thebes to a short distance to the south of the city, with the land beyond held by Kush. Some scholars believe that at the same time there was also a fourth power concentrated around Abydos and recent excavations there have uncovered tombs from the Second Intermediate period.

At one time it was thought that the Hyksos took control by invading, but more recent excavations show a different picture. After the Middle Kingdom collapsed and foreign trading missions ceased, outside traders made their way into Egyptian territory and more and more people migrated into the delta establishing themselves there. Tell el-Dab’a, the capital of the Hyksos, grew over time. The initial building phase was to the west, along the banks of the Pelusiac branch of the Nile. Excavating this site has been very challenging with layer upon layer of wet silt making it hard to distinguish between silt and mud brick. However, the initial building programme has been shown to include a palace, well structures and tombs.

Hostilities between the Egyptians and the Hyksos began under Seqenenre Tao who clearly died in battle as one of the severe wounds to his head can be identified as having been made by a Hyksos-shaped axe. When he died his wife, Ahotep, rallied the troops and he was succeeded by Kamose (possibly his son, or maybe his brother) then by his son Ahmose I. Mariette discovered Ahotep’s tomb in Dra Abu el-Naga, but this was at a time when control over finds was far less regulated than today and in the fight over the spoils her mummy and many other objects disappeared. However, from what remains of the finds today it is clear from the number of weapons buried in the tomb, together with her elaborate jewellery, that she had an important role in the expulsion of the Hyksos. International connections were also evident in a Minoan-style boat and Nubian flies of valour.

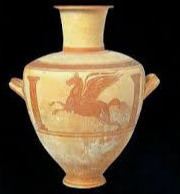

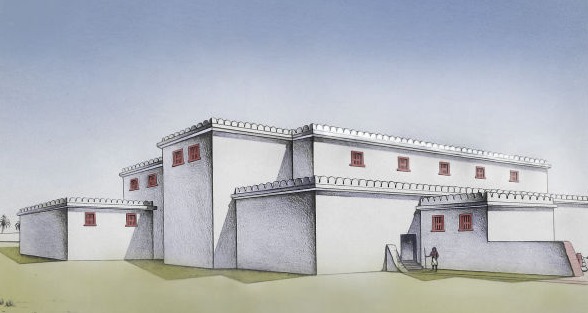

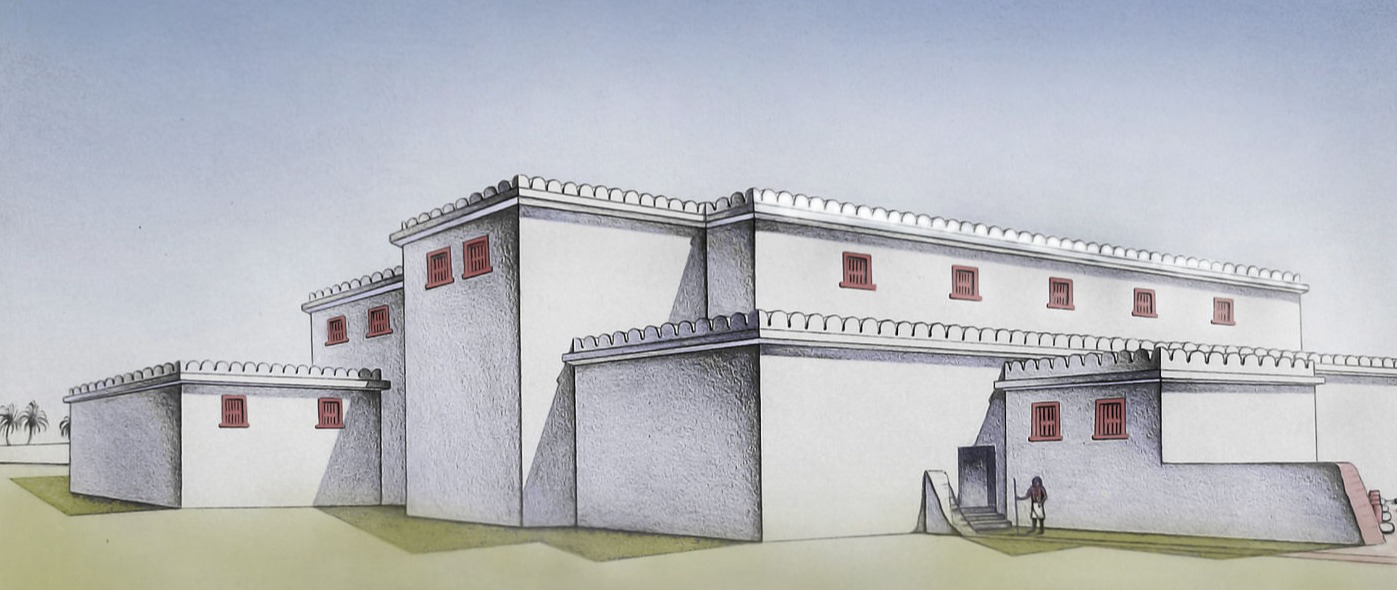

Under the reign of Seqenenre Tao the Thebans built a new campaign palace to the north of Thebes at Deir el-Ballas on the Qena bend. In a style that was later reflected at Amarna and Malqata, the site was constructed on virgin land along the desert edge of the Nile and comprised a royal palace, houses of the courtiers, a workmen’s village, a harbour, an administrative area and, at the southern end, a large structure originally called the south palace.

George Reisner was the first to excavate this site in 1900 and 1901, but sadly the notes of his work there have never been published. However, even before he commenced work there, a lintel had been found from the site, then apparently lost. Its whereabouts were unknown for many years, but happily it is now in the GEM. The construction of the north palace was made using a casemate foundation, which was paved over making a strong platform on which to build the second storey. It was decorated, though almost none of the decoration has survived. Unusually large bricks were used for the building which were one cubit long. Incorporated into the walls were large sections of ships, including part of a mast, which gave an interesting insight into the development of ship building techniques. From these pieces it was clear to see that construction had progressed from the tied method on Khufu’s boat, then dovetail joints into mortice and tenon joints with dowel pegs. Just outside the palace Reisner discovered a deposit of model offerings made of clay. They were beautifully made and painted, though not fired, and the range of objects was remarkably similar to those found in Ahotep’s tomb.

Reisner also excavated the houses, but unfortunately did not back-fill the site so what remains has deteriorated significantly since his time. However, more recent excavations discovered that his digging was not as deep as it could have been and objects have now been unearthed in the lowest levels. There were also small chapels for the workmen. Reisner had called the southern structure the south palace because of its immense size, but it is a large platform raised 25m above the plain, giving commanding views of the Nile and surrounding area.

The Kamose stela records how forces were combined to defeat the Hyksos and numerous ostraca recording the ships’ provisions and crews, include the names of Egyptian, Nubian and Asiatic sailors. The fleet sailed north to Avaris to defeat the Hyksos. After the victory the palace at Tell el-Dab’a seems to have been destroyed with two new structures built over the site, again in the strategic position overlooking the Nile where river traffic could be monitored.

Dr Lacovara’s work at Deir el-Ballas began in the 1980s, but he was asked to come back to the site as it suffered considerable damage from looting at the time of the revolution. The modern village was also encroaching and a new road had been laid down on the western side, leaving Deir el-Ballas sandwiched between the cultivation and the road. Thanks to a grant from ARCE he has been able to restore the southern viewing platform back to how it looked in Reisner’s time and work is currently progressing on the north palace. It is also intended that the enclosure wall will be restored. We were all delighted to learn that Dr Lacovara hopes that the site will be opened up to visitors in the next few years and, to this end, signs have been created together with the Ministry of Antiquities, though not yet erected. Co-Director Nick Brown has also produced educational pamphlets for the local people to engage them with this important site on their doorstep. Dr Lacovara is intending to publish Reisner’s work as well as the details of his own excavations in due course and acknowledged the great support he has received from many sources, as well as ARCE, for excavating at Deir el-Ballas.

December 2025

Ashley began by giving us information about exhibitions currently being held at National Museums Liverpool, with ‘Treasure: History Unearthed’ at Museum of Liverpool until 29th March 2026 and ‘Turner: Always Contemporary’ until 22nd February 2026 at the Walker Art Gallery.

His lecture covered the Old Kingdom objects in the World Museum collection from the period (approximately) 2686 to 2125 BC. The number of items from this period (about 410) form only a small part of the collection of 16,000 artefacts. During the 3rd Dynasty Djoser and Imhotep introduced radical changes to royal burials with the construction of the step pyramid. Sitting atop the escarpment at Saqqara this was visible from miles away and made a bold statement. Moving into the 4th Dynasty there was the transition to the true pyramid shape. This was a very clear demonstration of the king’s status and his special contracts with both the gods and his people. The resources required were enormous. In the 5th Dynasty the pyramids were smaller, but more consistent with an internal stepped structure surrounded and covered by smooth coating stones. Sahure’s mortuary temple had the greatest amount of decoration and some very unusual artwork. The small pyramid of Unas was the last of the 5th Dynasty, but the first to contain the pyramid texts aiding the king in his journey in the afterlife. The pyramid texts continued through the 6th Dynasty and, although the pyramids were smaller, they had very stylish architecture.

Ashley has placed the museum’s Old Kingdom objects into different categories and he described these, giving an example of the most highly prized item for each group.

Containers (173) – there is very little pottery, but some beautifully crafted vessels in other materials including an alabaster vase from an excavation in 1909 (when excavators were permitted to keep part of their finds). This vessel came to the museum in 1977.

Tools (145) – the number of individual tools is much higher, but in many cases a large number are grouped under one accession number. An example of this is a collection of 3rd to 6th Dynasty tools from Petrie’s mission at Hierakonpolis, which were excavated by F W Green in what appeared to be a workshop. Many of these were initially sent, still encased in mud, to Petrie’s friend Spurrell. When he received the crate, which appeared to just contain mud, he initially thought they were playing a joke on him – until Hilda Petrie told him to look a little more closely!

Art (17) – these 5th to 6th Dynasty objects mostly come from Garstang’s collection. He excavated some, but bought others and sadly some of the purchased items have no provenance.

Architecture (9) – there are fragments of pyramid texts, spells 266, 533 and 539 from Saqqara bought by Henry Wellcome.

Household items (5) – the most spectacular in this category is an ornate alabaster headrest (although strictly it was created for use in the tomb, rather than being an everyday object). This is from the Francis Danson collection.

Personal items (4) – these are mostly mirrors, with one special 6th Dynasty one from the Mayer collection, which includes an inscription.

Personal Ornaments (24) – mostly jewellery, with one particularly beautiful string of carnelian beads from an EEF excavation in 1897.

Religious (16) – the majority of these items are amulets, with one of the best coming from a 1901 excavation at Abydos.

Textiles (15) – these fragments are for the most part from Tarkhan, the same location as the lovely linen dress in the Petrie Museum.

Toys and Games (4) – some limestone balls are held, which come from the burial chamber of a Gizan mastaba tomb excavated by Petrie.

Human Remains (1) – the World Museum has just one example, from the 1904 University of Liverpool excavation near the Beni Hassan tombs.

The museum would currently have far more objects if it had not been for the disastrous events on the night of 3rd May 1941 when Liverpool was bombed. About 3000 objects were destroyed in the explosion and subsequent fire. It is only thanks to the thorough 1870s cataloguing by Charles Getty and Samuel Birch and the later, even more precise and detailed, cataloguing by Newberry and Peet together with student Meta Williams between 1910 and 1920, that it was possible to identify exactly what was lost in the fire. One of the most spectacular artefacts lost that night was a beautiful vessel bearing the name of Khufu. Some objects had previously been evacuated, but sadly not this one. ‘Losses’ also occurred from amongst the items which had been moved elsewhere, though a few of these have made their way back to the museum by one means or another.

The World Museum owes its existence to Joseh Mayer. He moved from Newcastle-under-Lyne to Liverpool and had amassed a range of interesting items from the Ancient World. His interest grew and over the years he became more and more serious about collecting. He bought items from many different collectors, some well-known such as Henry Salt and others who acquired objects on a much smaller scale. In 1867 his entire collection came to Liverpool Free Public Museums.

The jewel of the Old Kingdom artefacts is the stela of Niankhtet dating to the end of the 3rd Dynasty and part of Joseph Mayer’s collection, purchased by him from Sands. The stela has both raised and sunken relief and was crafted at the time when decorative themes, which had previously been the sole preserve of royalty, were just starting to be adopted by non-royals. The stela includes many of his titles and images of all the offerings Niankhtet hoped for in the afterlife, incorporating an extensive list of linens and also wine, which was a little unusual. But the most unusual thing about the stela is that it doesn’t include the actual offering formula itself.

Another absolute gem, smaller but equally spectacular, is a sacred oil tablet with 7 circular depressions; again from Mayer’s collection having been bought in 1850.

The largest Old Kingdom object is a 6th Dynasty door lintel with one jamb. This was gifted from the University of Liverpool by William McGregor and came from an 1850s excavation at Saqqara by Mariette. The inscriptions refer to festivals – start of the year festivals were very popular – and encourage everyone to make an offering, even just a voice offering if nothing else was to hand.

Amelia Edwards came to Liverpool at least twice when she was publishing collections in the North West. At that time she declared that the Egyptology collection in Liverpool was second only to that of the British Museum.